How it occurs

-

Design research

One critical way that survivorship bias can creep into the design process is through the participants we choose (or leave out) of design research. A lack of participant diversity will inevitably lead to a lack of data diversity. If you’re only considering one perspective, it will reduce the reliability of the data.

-

Design feedback

Design feedback is another crucial part of the design process and also one that survivorship bias can take hold. The best design is that which considers a diversity of perspectives, specifically in regards to the people who will be using it. For example, focusing too much on only the positive feedback from our peers is likely to result in solutions that aren’t resilient enough. If the team with which we are receiving feedback lacks diversity, so too will the input we receive during the design process.

When we focus too much on success stories, positive metrics, or ‘happy paths’ in our designs, we lose sight of how the design responds when things fail.

How to avoid

-

Factor in failure

While survivorship bias is common within the design process, there are ways to counter it as well. When we focus too much on success stories, positive metrics, or ‘happy paths’ in our designs, we lose sight of how the design responds when things fail. Consideration of only positive feedback is likely to lead to a very one-sided design approach. It’s best to factor in failure, consider where things can go wrong, centralize the edge cases in the design process, and seek out diverse perspectives during design reviews. In other words, we can make our designs more resilient by considering the unhappy path just as thoroughly as the happy one. In the process of designing for the less ideal scenarios, we address the fundamental features needed for everyone.

-

Recognize the limits of quantitative data

We must remember quantitative data is only relevant to the actions currently available and therefore has the potential to limit our thinking. As Erika Hall points out in Just Enough Research, “By asking why we can see the opportunity for something better beyond the bounds of the current best”. We should consider what the quantitative data isn’t telling us to make more informed design decisions.

Case study

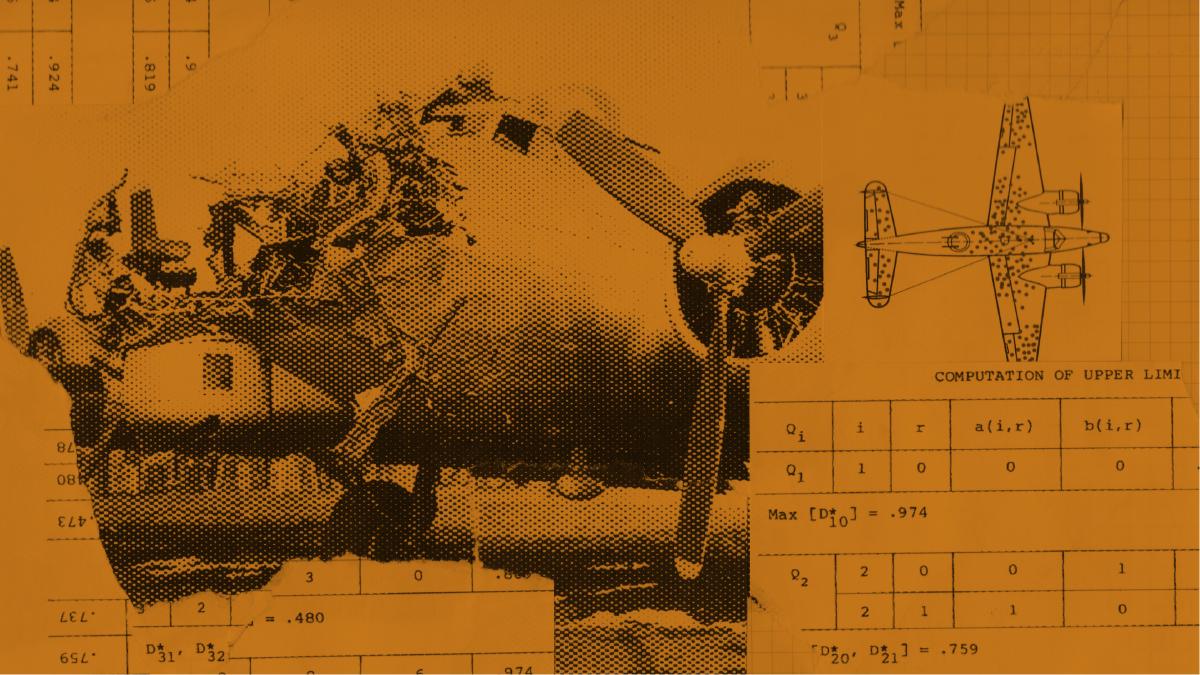

Abraham Wald’s Work on Aircraft Survivability

During World War II, the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University was asked by the U.S. military to examine the damage done to bombers that had returned from missions. Their objective was to determine where armor could be added to the bombers to increase the protection from the flak and bullets. Planes that returned were carefully examined and damage was compared across all the planes. The consensus was that additional armor should be added to the areas of the planes that show the most common patterns of damage: the wings, tailfin, and middle of the planes.

Luckily, a statistician on the project by the name of Abraham Wald countered this conclusion by pointing out that the planes being examined were only those that survived, therefore calculations were missing a critical set of data (the planes that didn’t make it back). As a result, Wald recommended that armor get added to the areas that showed the least damage to reinforce the most vulnerable parts of the planes.

The case study of World War II bombers highlights our tendency to concentrate on the people or things that made it past a selection process and overlook those that do not, typically because of their lack of visibility. This can lead to false conclusions in several different ways. This tendency is known as survivorship bias and it can show up during a critical part of the design process.