How it occurs

People often overestimate the degree to which other people will agree, think, and behave the way they do.

How to avoid

-

Identify your assumptions

The first step is to identify the assumptions you or your team are making about the intended users. Whether it’s assumptions related to their needs, pain points, or how they accomplish tasks, we must begin by acknowledging the things we are assuming. Once assumptions have been identified, they should be prioritized by the amount of risk they carry and investigated via tests. -

Test with real users

The next step is to conduct user interviews and usability tests with the intended audience. User interviews are critical in understanding the decision-making process, needs and frustrations, opportunities, and how steps are taken to complete tasks. Usability tests are also quite effective for understanding how actual users respond to your designs by watching them use these designs and challenging your assumptions.

Case study

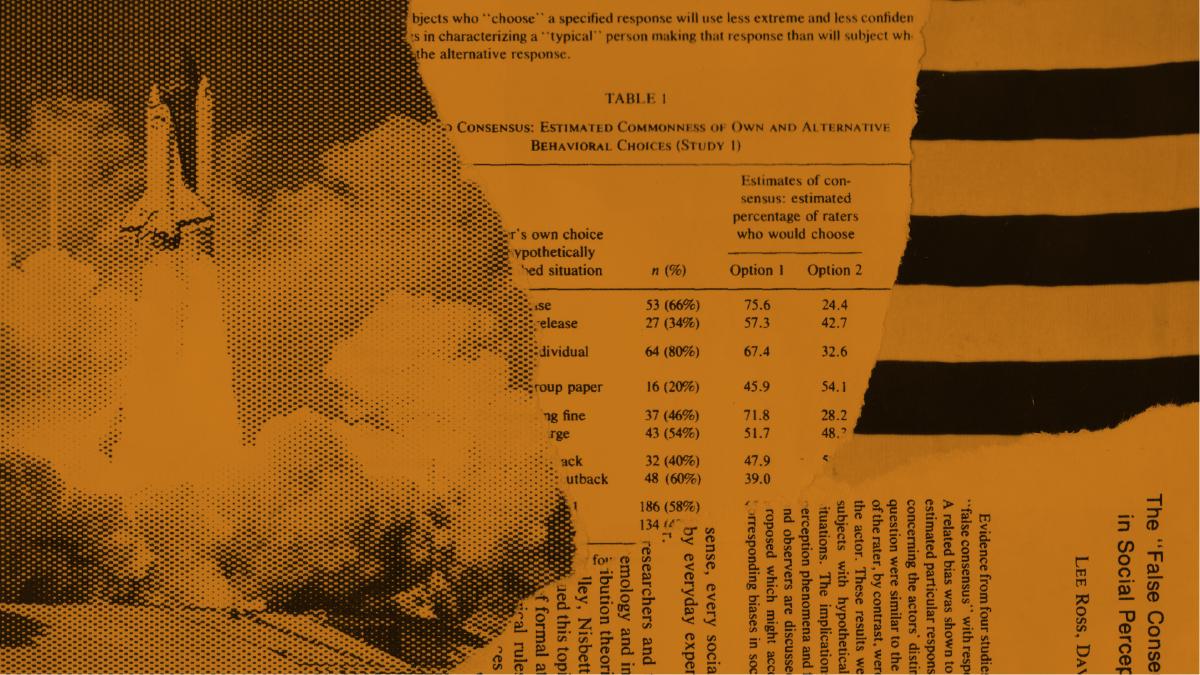

False Consensus Effect: An Egocentric Bias in Social Perception and Attribution Processes

A 1976 study conducted at Stanford University presented participants with hypothetical situations and asked them to determine what percentage of people would make one of two choices. For example, one situation asked participants to determine what percentage of their peers would vote for a referendum that allocated large sums of money towards a revived space program with the goal of manned and unmanned exploration of the moon and planets nearest Earth. Some additional context was given, explaining that supporters would argue that this would provide jobs, spur technology, and promote national pride and unity. In contrast, opponents argue that a space program will increase taxes or else drain money from important domestic priorities while not achieving the goals of the program.

Once the participants provided their estimate, they were asked to disclose what they would do given the situation and fill out two questionnaires about the personality traits of those who would make each of the two choices. Researchers concluded that the participants not only expected that most of their peers would make the same choices they did but assumed those that opted for the opposite choice had extreme personality traits.

The study highlights our tendency to assume that our personal qualities, characteristics, beliefs, and actions are relatively widespread while alternate points of view are rare, deviant, and more extreme. This bias, known in psychology as the false-consensus effect, can skew our thinking and negatively influence design decisions.