Be aware of your decision frame

How it occurs

-

Question framing

The phrasing of questions during user interviews or usability tests can have a significant impact on the response of participants.

-

Presentation research findings

The frame in which we choose to present research findings from user interviews or usability tests can easily influence how the research is interpreted.

-

Design feedback

Another potential entry point for framing during the design process is when receiving design feedback. Overly specific feedback can frame up the problem in a way that limits the design solution, or influences it in a way that leads to overlooking other important considerations.

While it may be tempting to jump into solutions right away, taking a little more time to think through context will significantly impact how we interpret the data.

How to avoid

-

Think through the context

Solutioning when we should be still gathering information can be a constant challenge for team members, especially for designers. While it may be tempting to jump into solutions right away, taking a little more time to think through context will significantly impact how we interpret the data. It’s only once we spend ample time with the gathered data that we can begin to synthesize useful insights from it and identify patterns that aren’t as obvious on the surface.

-

Gather more context

Instead of making a decision based on however much data you have, wait until you have enough to make an informed decision. Sometimes research uncovers what we need to learn more about. You’ll know you have enough information to make an informed decision when you have a clear idea of the problem and sufficient information to begin on a solution.

-

Switch your view

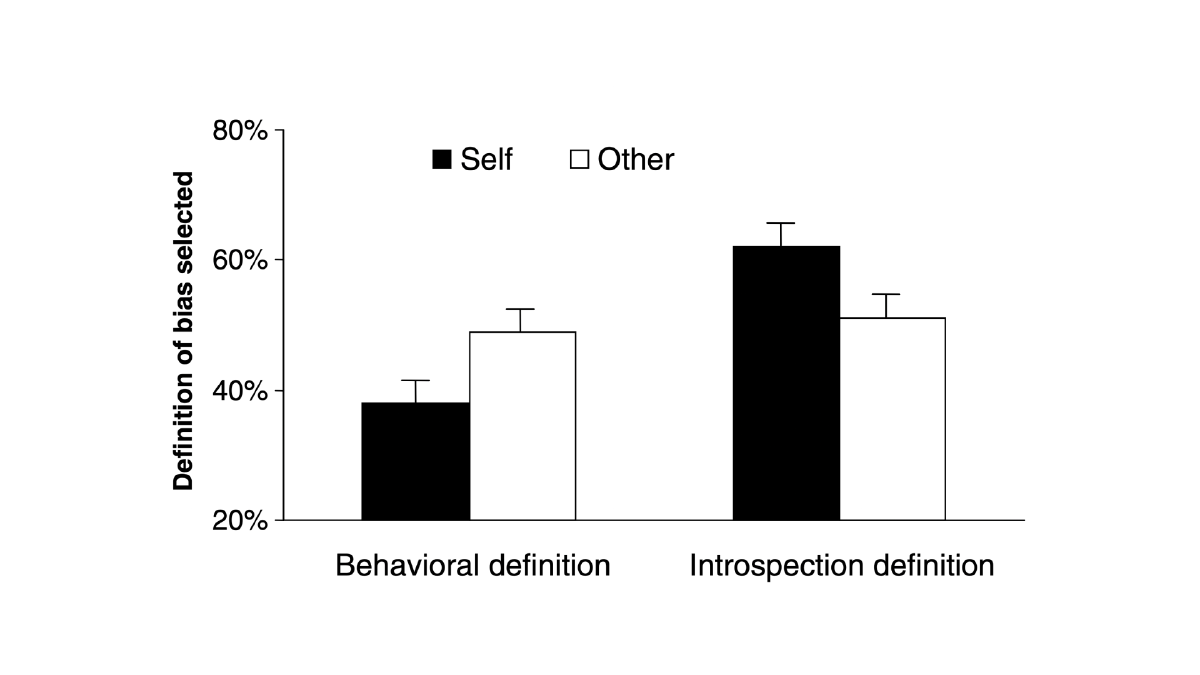

Another way to diagnose if your opinion is being influenced by framing is to switch up your point of view. You can do this by reversing a data point from a success rate to a failure rate, or taking the opposite approach to articulating a problem. The point of this is to perceive the data from another angle to avoid emphasis or exclusion of specific information.

Case study

The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice

In 1981, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman explored how different phrasing affected participants’ responses to a choice in a hypothetical life and death situation. In the study, participants were asked to choose between two treatments for 600 people affected by a deadly disease. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, whereas treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die. This choice was then presented to participants either with positive framing, i.e. how many people would live or with negative framing, i.e. how many people would die. Treatment A was chosen by 72% of participants when it was presented with positive framing (“saves 200 lives”) dropping to 22% when the same choice was presented with negative framing (“400 people will die”).

The choice of the participants in this study highlights our tendency to make decisions based on whether the options are presented with positive or negative connotations; e.g. as a loss or as a gain. In psychology, this is known as the framing effect and it affects all aspects of the design process, from interpreting research findings to selecting design alternatives.